The 18 flags of San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza

San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza, between City Hall and the Main Library, is a beautiful public space with a bunch of flag poles. In addition to a handful in the corners of the plaza, there are two rows of nine of them along the central walkway, each flying a different flag.

Many of those flags are unusual, and I’m surprised not to find a catalogue of them anywhere. Here’s what I could find about the flags there, starting from the southwestern corner (closest to City Hall) and continuing around counterclockwise. It’s a bit hard to see the field of the flags, so some of these might be slightly incorrect.

Southern row, west to east:

- On the southwestern corner is, I think, the first official US flag with stars, and has 13 stars and stripes. This one was flown from 1777 to 1795, and replaced by the Star-Spangled Banner, or the Great Garrison Flag, which had 15 stars and, uniquely, 15 stripes. That flag flew during the War of 1812 and was the one about which Francis Scott Key wrote his famous poem.

- The Pine Tree Flag, also known as the Appeal to Heaven Flag, shows a pine tree with that caption above. The phrase “An Appeal to Heaven” was popularized by Locke. This flag was used largely during the Revolutionary War, and also by the Massachusetts Navy (and privateers hired to assist them).

- Another American Flag with a small number of stars. I think this one is the short-lived 20-star flag, which flew from 1818-1819.

- Up next we’ve got the Flag of Texas. I don’t know why that would be flying in this set, but it looks unambiguously like that: the left quadrant is a blue field with a single white star, and the rest of the flag is a white stripe over a red one. Maybe it has something to do with the next one, which is:

The original California Bear Flag, which is much simpler than the modern version. Both, however, include a bear and a star, and that star comes from an earlier flag called the California Lone Star Flag, flown during a failed rebellion in 1836. The name and star are said to be inspired by Texas, so maybe that’s why that state got included.

The original California Bear Flag, which is much simpler than the modern version. Both, however, include a bear and a star, and that star comes from an earlier flag called the California Lone Star Flag, flown during a failed rebellion in 1836. The name and star are said to be inspired by Texas, so maybe that’s why that state got included.- The next one’s an American flag, and to my eye it looks like the 36-star version that flew again for only a few years between 1865 and 1867, or between the inclusion of Nevada and Nebraska into the country. Weird flag choices, guys.

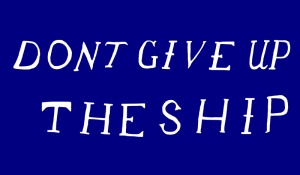

Next is a cool one, the Don’t Give Up the Ship Flag flown by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry on the USS Niagara during the War of 1812 and a heroic victory at Erie 200 years ago this week. The words themselves were the dying command of of Perry’s friend James Lawrence, who issued them during a battle that didn’t go quite as well. In its day, the slogan was a well-known battle cry, but I’ve never seen the flag anywhere else.

Next is a cool one, the Don’t Give Up the Ship Flag flown by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry on the USS Niagara during the War of 1812 and a heroic victory at Erie 200 years ago this week. The words themselves were the dying command of of Perry’s friend James Lawrence, who issued them during a battle that didn’t go quite as well. In its day, the slogan was a well-known battle cry, but I’ve never seen the flag anywhere else.- Another US flag, which looks to me like the 48-star version that was flown from 1912 to 1959. Until July 4, 2008, this was the longest-used version of the flag in history.

- The last flag on the southern row is the current American Flag, with 50 stars and 13 stripes.

Northern row, east to west:

- On the northeast corner is a flag with a British Union cross in the canton and a red field with the word “Liberty” in white. This one’s kind of a mystery to me. It’s probably just a slight variation on the Taunton Flag, which was a Revolutionary flag first raised in Taunton, Massachusetts, but I can’t find any evidence of a version that doesn’t have the full “Liberty and Union” text. Both flags are modified from the Red Ensign, the flag that was flown by civilian merchant ships.

- The next one in from there is a historical Flag of New England, which is likely another one that flew during the Revolutionary War. It’s got a green pine tree in a white field on the upper-left corner, and is otherwise red. The flag seen in John Trumbull’s famous Bunker Hill painting appears to have a version of this flag right in the middle.

- The next one’s a variant of the Pine Tree Flag, this one with the words “Liberty Tree” at the top and “An Appeal to God” at the bottom. It was used during the Revolutionary War, and I couldn’t readily find information about why the other version seems a bit more common.

- The Moultrie Flag features the word “Liberty” in a white crescent on the corner of a blue flag. It’s another Revolutionary War flag, but has since become associated with South Carolina, and serves as the basis for that state’s flag.

- The next one’s a classic, the Gadsden Flag, with the rattlesnake saying “Don’t Tread On Me.” Of course today this flag may be best known as a symbol of the Tea Party, which is kind of a funny association to have out in front of San Francisco’s City Hall.

- The next flag is a modern Flag of California. The bear on this flag was modeled after an actual bear named Monarch that, after its death in 1911, was stuffed and is still on display in the Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park.

The Grand Union Flag, also known as the Continental Colors, is usually considered the first official flag of the United States. It’s got the British Union cross up in the left corner, which is slightly different from today’s version in that it doesn’t have the red on the diagonal. That’s from Ireland’s St. Patrick’s Cross, which wasn’t incorporated until 1800.

The Grand Union Flag, also known as the Continental Colors, is usually considered the first official flag of the United States. It’s got the British Union cross up in the left corner, which is slightly different from today’s version in that it doesn’t have the red on the diagonal. That’s from Ireland’s St. Patrick’s Cross, which wasn’t incorporated until 1800.- The next flag is the Betsy Ross Flag, with the 13 stars arranged in a circle. There are all kinds of fun legends about the extent of Betsy Ross’ actual involvement in the design and manufacture of this flag, but in any case it’s still one of the more recognizable symbols of the Revolutionary War, but apparently there’s not enough evidence to determine whether it was any more popular than other flags with 13 stars that were available at the time.

- Finally, the Bennington Flag, which features 13 7-pointed stars and a big “76” in the middle of the blue field. There’s a legend that the original Bennington flag was carried off the battlefield by Nathaniel Fillmore, and handed down through his family into the eventual possession of President Millard Fillmore, after whom the street in San Francisco is named. But that story falls pretty firmly into the category of legend, as historians aren’t generally convinced that this flag flew at the Battle of Bennington at all.