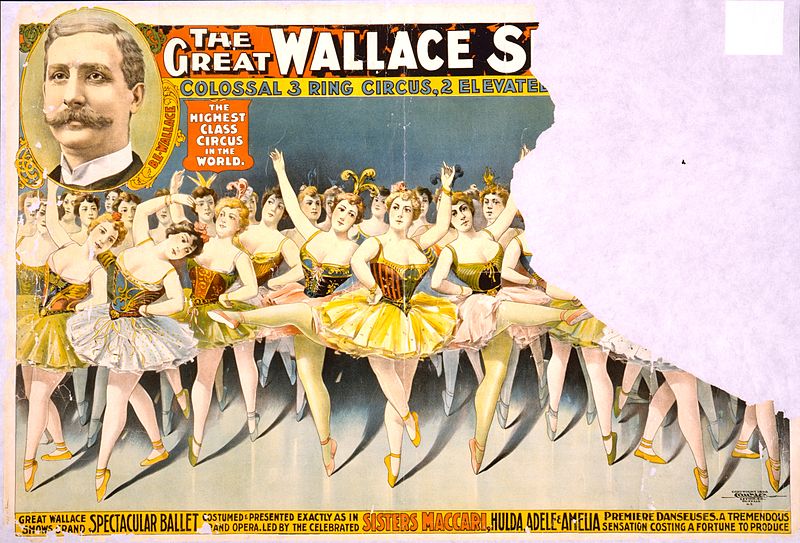

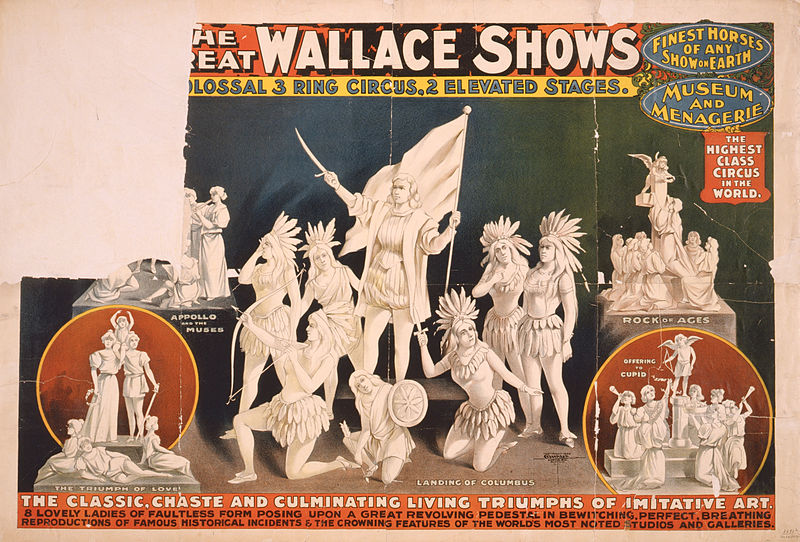

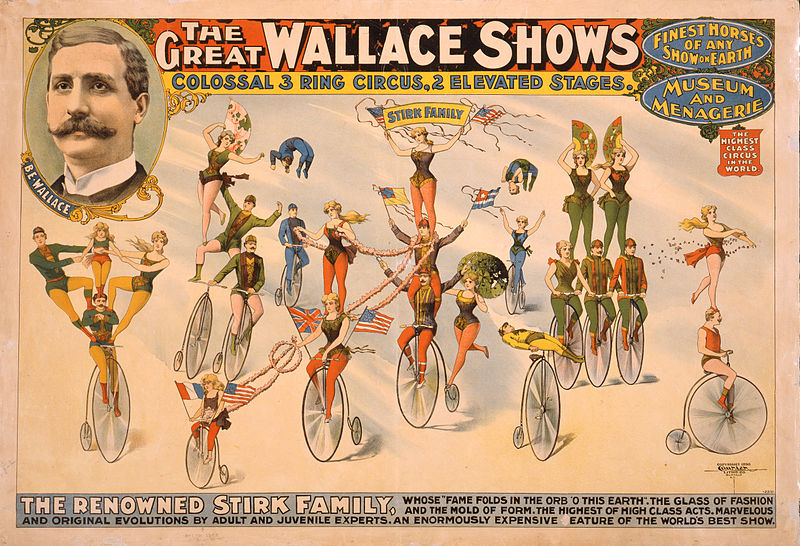

3 circus posters that changed the face of copyright law

The 1903 Supreme Court ruling in Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co. was a hugely influential for turn-of-the-century copyright. Bleistein was an employee of a company that had designed circus posters for The Great Wallace Shows. Donaldson was a competitor of that company, and agreed to print a subsequent run of those same posters without authorization.

At issue was whether these posters—which were certainly creative, but just as certainly commercial—could be restricted by copyright. By ruling in favor of the plaintiff, the Supreme Court made it clear that the bar for copyright eligibility is not some abstract notion of artistic merit, but simple originality. Commercial speech was just as qualified as fine art. From Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr’s majority opinion:

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme, some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke. It may be more than doubted, for instance, whether the etchings of Goya or the paintings of Manet would have been sure of protection when seen for the first time. At the other end, copyright would be denied to pictures which appealed to a public less educated than the judge. Yet if they command the interest of any public, they have a commercial value — it would be bold to say that they have not an aesthetic and educational value — and the taste of any public is not to be treated with contempt. It is an ultimate fact for the moment, whatever may be our hopes for a change. That these pictures had their worth and their success is sufficiently shown by the desire to reproduce them without regard to the plaintiffs’ rights.

I’d read about this case many times, but had never seen high quality copies of the three posters at the heart of the matter. After a bit of digging, I found copies in the Library of Congress, which have been scanned at an extremely high resolution. I’ve cropped, cleaned up, and color-corrected the images in this post, but if you’ve got any interest I strongly recommend downloading the huge TIFF files from the LoC. Descriptions of each image by Holmes himself:

- an ordinary ballet

- a number of men and women, described as the Stirk family, performing on bicycles

- groups of men and women whitened to represent statues

Nowadays it seems obvious that these creative and original images would be subject to copyright. It’s a nice reminder that the assumptions of today are likely just as brittle as the ones that affected these colorful posters over a century ago.