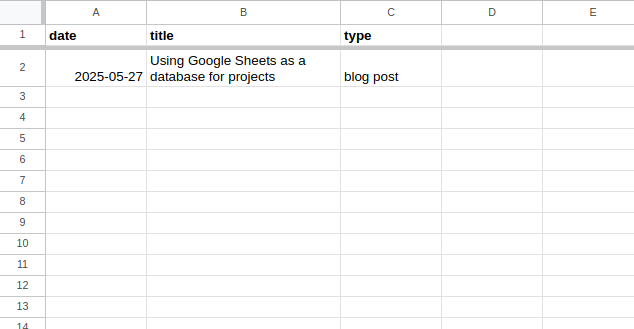

Using Google Sheets as a database for projects

As a software developer who enjoys working on hobby projects, especially with less technical collaborators, I have found myself using Google Sheets as a good-enough database in a lot of circumstances. I have lots of qualms about having the biggest of Big Tech in a load-bearing spot on these projects, but the practical benefits and the existence of a reasonable exit route have helped to quiet them.

One good example project is Daily Crossword Links, a newsletter started by Matthew Gritzmacher to compile, as its name suggests, links to each day’s published crosswords. The newsletter always includes mainstream and independent outlets (down to individual bloggers). When Matthew and I first spoke about it, he was putting it together each day by hand, checking and copying text from dozens of sites while referring to a Google Sheet of puzzle sources that he’d made. We started from that Google Sheet, and I was able to automate a lot of that process, ultimately producing a draft each day that he (and eventually other editors) could clean up for publication—and to this day, the source of truth for what goes into those drafts is a Sheet.

It’s a recipe I’ve followed a bunch of times now, and when I’m discussing it with collaborators, I usually come back to the same list of benefits.

- Everybody already has an account, and they are comfortable with the collaboration workflows. That doesn’t mean they’re the ideal workflows for any given situation, or even that they’re very good, but at least they’re familiar. So when the Daily Crossword Links project expanded from one editor to a handful of volunteers, they were able to manage this through invitations to the spreadsheet, without me having to build any new auth or permissions model. Besides collaboration, they also have pretty robust version controls, and other mechanisms in place to prevent data loss.

- Spreadsheets themselves are really powerful tools, including for automation. The crossword newsletter crew now has a bunch of functions to fill in dynamic dates and titles and things like that, and they don’t need “developer time” to expand those. On another project I’m working on, the proprietor (who is a much more sophisticated programmer than I am!) wrote a Google App Script to update her data. And even for less technical users, I can write formulas that are less intimidating—and provide real-time feedback—than the equivalent Python would be.

- There are clients for every device, which means editing is always going to be more-or-less reasonable. Editing a spreadsheet from a cell phone is not great, but it’s not an experience I’m shoving down their throat. Similarly, people know how to read a spreadsheet, and it’s much more inviting than an equivalent table of data.

- Spreadsheets also enforce some data discipline in ways that don’t feel overbearing. With most projects I’m immediately converting the data into JSON or YAML, which to their credit are mostly readable (if intimidating). Creating a new object in either format, though, requires cutting and pasting and sometimes interacting with the vagaries of the specs. On the other hand, a new row in a spreadsheet has labeled columns and example data right next to it. Not to mention, conditional formatting can even highlight missing or malformed data if necessary. All of this makes the upgrade path out of a Sheet clear, if need be; and in most cases, a CSV export would work as a drop-in replacement, in a pinch.

- Combining those last two points: One pattern I’ve used successfully is rigging up a Google Sheets “database” to a Form, which is a totally familiar interface that can do all kinds of validation and provide default values.

There are of course drawbacks. To make one obvious point, a spreadsheet is not really the right data structure for some kinds of projects. Text formatting is a bit of a bear to deal with, and if you need more than two dimensions of data (including nesting or any kind of relational component), things get very hacky fast. (It helps that you can have multiple sheets within a Sheet, and they can refer to each other in formulas.)

And of course, a lot of these advantages would be moot if there weren’t good tooling. For my Python projects, I’ve had a great experience with gspread for both reading and writing data. I haven’t really had to look into what the ecosystem is like elsewhere, but I expect that this many years into Google Sheets there’s pretty good support everywhere.

From a practical standpoint, the existence of good tooling like that means that my exposure to Google Sheets is pretty minimal: I hit the API to download live data, and in some cases to make updates, but the data otherwise feels pretty native. If I ever had to migrate a particular project away, it would be disruptive for my collaborators learning a new workflow, but it would be pretty easy for me to swap out gspread for a regular parser of a standard data format.